Chapter 2.3

Post-cranial skeletal system

A. Axial Skeleton

Introduction

The axial skeleton is the central architectural framework of vertebrates, providing structural support, protecting vital organs, and facilitating locomotion. Its evolution marks a critical transition in vertebrate history, enabling the colonization of diverse ecosystems from aquatic to terrestrial environments. This lecture explores the evolutionary significance of the endoskeleton, defines the axial skeleton, details its components and functions, and traces major evolutionary milestones across vertebrate lineages.

I. Evolutionary Importance of the Endoskeleton

The endoskeleton, an internal bony or cartilaginous framework, is a hallmark of vertebrates. Its emergence catalyzed key evolutionary advancements:

1. Structural and Functional Advantages

- Support and Mobility: Enabled larger body sizes and complex movements by anchoring muscles.

- Protection: Shielded delicate organs (brain, spinal cord, heart, lungs) from mechanical damage.

- Efficient Respiration: Ribs facilitated the evolution of costal breathing in terrestrial vertebrates.

- Neural Coordination: Vertebral column safeguarded the spinal cord, enhancing nervous system complexity.

2. Contrast with Exoskeletons

- Flexibility: Unlike rigid exoskeletons (e.g., arthropods), the endoskeleton allows continuous growth and dynamic movement.

- Energy Efficiency: Reduced metabolic cost of moulting, enabling sustained activity.

3. Evolutionary Drivers

- Predator-Prey Arms Race: Reinforced skeletons improved predatory efficiency and defensive capabilities.

- Terrestrial Transition: Adaptations like weight-bearing vertebrae and rib cages supported life on land.

II. Definition of the Axial Skeleton

The axial skeleton comprises the skull, vertebral column, ribs, and sternum (in tetrapods). It distinguishes vertebrates from invertebrates and serves as the body’s central axis.

1. Embryonic Origins

- Derived from somites (mesodermal segments) and neural crest cells.

- Notochord: A flexible rod in early chordates, replaced by vertebrae in most vertebrates.

2. Divisions of the Skeleton

- Axial Skeleton: Central axis (skull, vertebrae, ribs, sternum).

- Appendicular Skeleton: Limbs and girdles (pectoral, pelvic).

III. Components of the Axial Skeleton and Their Functions

1. Skull

- Structure: Composed of neurocranium (brain case) and splanchnocranium (visceral arches).

- Functions:

- Protects the brain and sensory organs (eyes, ears).

- Facilitates feeding via jaw mechanics.

- Anchors muscles for head movement and facial expression (mammals).

2. Vertebral Column

- Structure: Series of vertebrae separated by intervertebral discs. Regions include cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and caudal.

- Functions:

- Supports body weight and maintains posture.

- Protects the spinal cord.

- Provides attachment points for muscles and ribs.

3. Ribs

- Structure: Long, curved bones extending from thoracic vertebrae.

- Functions:

- Protect thoracic organs (heart, lungs).

- Assist in respiration by expanding the chest cavity.

- Anchor muscles for posture and locomotion.

4. Sternum

- Structure: Flat bone in the thoracic region (tetrapods).

- Functions:

- Stabilizes rib cage during breathing.

- Attaches pectoral muscles (e.g., flight muscles in birds).

IV. Evolutionary Milestones of the Axial Skeleton

1. Early Chordates and the Notochord

- Cambrian Period (~500 MYA): Protochordates (e.g., Haikouichthys) possessed a notochord for flexibility.

- Agnathans (Jawless Fish): Lampreys and hagfish retained notochords with rudimentary vertebral elements.

2. Emergence of Vertebrae in Gnathostomes

- Cartilaginous Fish (Chondrichthyes): Sharks evolved calcified vertebrae for enhanced mobility.

- Bony Fish (Osteichthyes): Ossified vertebrae provided structural reinforcement for diverse swimming modes.

3. Transition to Terrestrial Life

- Lobe-Finned Fish (Sarcopterygii): Robust vertebrae and ribs in Eusthenopteron preadapted for weight-bearing.

- Early Tetrapods (e.g., Acanthostega): Strengthened cervical and thoracic regions to support limbs and head movement.

4. Amniote Diversification

- Reptiles:

- Diapsids: Flexible cervical vertebrae (e.g., snakes) for prey capture.

- Archosaurs: Fused vertebrae in dinosaurs (e.g., Tyrannosaurus) for stability during bipedalism.

- Birds:

- Synsacrum: Fused pelvic vertebrae for flight balance.

- Hollow Vertebrae: Reduced weight without sacrificing strength.

5. Mammalian Innovations

- Regional Differentiation: Cervical (7 vertebrae in most mammals), thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and caudal regions.

- Intervertebral Discs: Cartilaginous cushions for shock absorption.

- Secondary Palate: Separated nasal and oral cavities, enabling efficient breathing while chewing.

V. Functional Adaptations Across Vertebrates

1. Aquatic Vertebrates

- Fish: Streamlined vertebrae and ribs for undulatory swimming.

- Marine Mammals (e.g., whales): Reduced hindlimb skeleton; elongated thoracic region for diving.

2. Terrestrial Tetrapods

- Amphibians: Simplified ribs for buccal pumping (respiration).

- Mammals: Rigid thoracic cage with a diaphragm for negative-pressure breathing.

3. Flight and Arboreal Life

- Birds: Keeled sternum for flight muscle attachment; fused caudal vertebrae (pygostyle) for tail feathers.

- Primates: Flexible lumbar vertebrae for arboreal locomotion.

Conclusion

The axial skeleton is a testament to vertebrate evolutionary ingenuity, underpinning survival in diverse habitats. From the notochord of early chordates to the specialized vertebrae of mammals, its adaptations reflect responses to ecological challenges and functional demands. Understanding its structure and evolution provides profound insights into vertebrate biology, paleontology, and biomechanics.

B. Appendicular Skeleton

Introduction

The appendicular skeleton consists of the bones of the limbs and their supporting girdles (pectoral and pelvic), playing a crucial role in locomotion, stability, and manipulation of the environment. Unlike the axial skeleton, which provides central support, the appendicular skeleton is primarily involved in movement and interaction with the external world. This lecture covers definition of the appendicular skeleton, parts and functions of the appendicular skeleton, modifications from fish to mammals, and major evolutionary milestones in vertebrate appendicular skeletons.

I. Definition of the Appendicular Skeleton

The appendicular skeleton includes:

- Paired fins/limbs (forelimbs and hindlimbs)

- Girdles (pectoral and pelvic) that attach limbs to the axial skeleton

Key Features:

- Derived from mesodermal somites and neural crest cells

- Varies across vertebrates based on locomotion (swimming, flying, walking)

- Evolutionarily dynamic, showing major transitions from fins to limbs

II. Parts of the Appendicular Skeleton and Their Functions

1. Pectoral Girdle (Shoulder Girdle)

- Composition:

- Fishes: Coracoid, scapula, and cartilage (e.g., in sharks)

- Tetrapods: Clavicle, scapula, and sometimes interclavicle (e.g., reptiles)

- Mammals: Scapula and clavicle (reduced or absent in some, like ungulates)

- Functions:

- Anchors forelimbs/fins to the axial skeleton

- Provides muscle attachment for limb movement

- Absorbs shock during locomotion

2. Pelvic Girdle (Hip Girdle)

- Composition:

- Fishes: Reduced or absent (except in some lobe-finned fish)

- Tetrapods: Ilium, ischium, pubis (fused in birds and some mammals)

- Mammals: Strongly fused for weight-bearing

- Functions:

- Supports hindlimbs

- Transmits force during locomotion

- Protects reproductive and excretory organs

3. Forelimbs and Hindlimbs

A. Basic Structure (Tetrapod Limb Plan)

- Stylopodium (upper limb): Humerus (forelimb), Femur (hindlimb)

- Zeugopodium (mid-limb): Radius/Ulna (forelimb), Tibia/Fibula (hindlimb)

- Autopodium (distal limb): Carpals/Metacarpals/Phalanges (forelimb), Tarsals/Metatarsals/Phalanges (hindlimb)

B. Functional Adaptations

- Running (Cursorial): Elongated limbs (e.g., horses, deer)

- Flying (Volant): Modified forelimbs into wings (e.g., bats, birds)

- Swimming (Aquatic): Flippers (e.g., whales, penguins)

- Grasping (Prehensile): Opposable digits (e.g., primates, chameleons)

III. Modifications of the Appendicular Skeleton from Fishes to Mammals

1. Fishes (Pisces)

- Pectoral Fins: Supported by radials and cartilaginous rays (Chondrichthyes) or bony rays (Osteichthyes)

- Pelvic Fins: Often small, used for stabilization

- Lobe-finned Fishes (Sarcopterygii): Muscular fins with bony elements (precursor to tetrapod limbs)

2. Amphibians (Transition to Land)

- Pectoral Girdle: Partially ossified, still cartilaginous in some areas

- Pelvic Girdle: Strengthened for weight-bearing

- Limbs: Short, robust (e.g., frog hindlimbs for jumping)

3. Reptiles

- Pectoral Girdle: Well-developed, often with a sternum

- Pelvic Girdle: Fused ilium, ischium, pubis (e.g., dinosaurs)

- Limbs: Varied—crawling (lizards), bipedal (theropods), or reduced (snakes)

4. Birds

- Pectoral Girdle: Keeled sternum for flight muscle attachment

- Forelimbs: Modified into wings (humerus, radius, ulna, fused carpals)

- Pelvic Girdle: Synsacrum (fused vertebrae for flight balance)

5. Mammals

- Pectoral Girdle: Reduced clavicle in fast runners (e.g., horses)

- Pelvic Girdle: Strong, fused for weight-bearing

- Limbs: Extreme specialization (e.g., bat wings, whale flippers, human hands)

IV. Major Evolutionary Milestones in the Appendicular Skeleton

1. Origin of Paired Fins (~500 MYA)

- Early Jawless Fish (Ostracoderms): No paired fins

- Gnathostomes: Development of pectoral and pelvic fins (e.g., placoderms)

2. Lobe-Fins to Limbs (~375 MYA)

- Sarcopterygians (e.g., Eusthenopteron): Muscular fins with homologous bones to tetrapod limbs

- Transitional Forms (e.g., Tiktaalik): Fin rays replaced by digits

3. Terrestrial Adaptations (~360 MYA)

- Early Tetrapods (e.g., Acanthostega): Eight digits, weak girdles

- Amniotes: Stronger limbs for efficient land locomotion

4. Specializations in Dinosaurs and Birds (~230 MYA)

- Theropods: Bipedalism, hollow bones

- Birds: Wings, fused bones for flight

5. Mammalian Diversification (~200 MYA–Present)

- Cursorial Adaptations: Digitigrade/unguligrade limbs (e.g., deer, horses)

- Flying Mammals (Bats): Elongated fingers supporting wing membranes

- Aquatic Mammals (Whales): Flippers, reduced hindlimb

V. Functional and Ecological Implications

- Locomotor Efficiency: Limb structure reflects speed, agility, and habitat

- Predator-Prey Dynamics: Limb specialization aids in hunting or evasion

- Evolutionary Trade-offs: Flight in birds vs. running in mammals

Conclusion

The appendicular skeleton is a cornerstone of vertebrate evolution, enabling diverse locomotor strategies from swimming to flight. Its modifications reflect adaptive responses to ecological challenges, illustrating the dynamic interplay between form and function.

C. Joints (both axial & appendicular and their types)

Introduction

Joints, or articulations, are structures where two or more bones meet, enabling movement, stability, and mechanical support. They are classified based on structure, function, and mobility, playing a crucial role in vertebrate locomotion, feeding, and posture. This lecture covers definition and classification of joints, types of joints and their functions, Comparative anatomy of joints in axial & appendicular skeletons (fish to mammals), and Major evolutionary milestones in joint development.

I. Definition of Joints

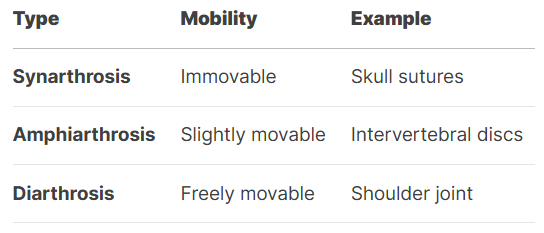

A joint is a connection between bones or cartilage, facilitating movement or providing structural support. Joints vary in mobility:

- Synarthroses (immovable)

- Amphiarthroses (slightly movable)

- Diarthroses (freely movable)

Functional Importance:

- Locomotion: Limb joints enable walking, swimming, flying.

- Protection: Skull sutures shield the brain.

- Feeding: Jaw joints allow biting/chewing.

II. Types of Joints and Their Functions

1. Structural Classification

A. Fibrous Joints (Synarthroses)

- Bones connected by dense connective tissue.

- Types:

- Sutures (e.g., skull bones in mammals)

- Syndesmoses (e.g., tibia-fibula interosseous membrane)

- Gomphoses (e.g., teeth in sockets)

- Function: Provide stability, resist mechanical stress.

B. Cartilaginous Joints (Amphiarthroses)

- Bones joined by cartilage.

- Types:

- Synchondroses (hyaline cartilage, e.g., growth plates)

- Symphyses (fibrocartilage, e.g., pubic symphysis)

- Function: Shock absorption, limited movement.

C. Synovial Joints (Diarthroses)

- Most mobile, enclosed in a synovial capsule.

- Types (by movement):

- Hinge (elbow, knee)

- Ball-and-socket (hip, shoulder)

- Pivot (atlantoaxial joint)

- Gliding (wrist, ankle)

- Saddle (thumb carpometacarpal)

- Condyloid (wrist radiocarpal)

- Function: Enable complex movements (running, grasping).

2. Functional Classification

III. Comparative Anatomy of Joints in Vertebrates

1. Axial Skeleton Joints

A. Fishes (Pisces)

- Skull: Mostly fused (synarthroses) for streamlined swimming.

- Vertebrae: Amphicoelous (biconcave) with notochord remnants, limited flexibility.

B. Tetrapods (Amphibians to Mammals)

- Skull:

- Amphibians: Kinetic skulls with movable joints for swallowing prey.

- Mammals: Synostosis (fused sutures) for brain protection.

- Vertebral Column:

- Intervertebral discs (symphyses) for shock absorption.

- Zygapophyses (synovial joints) in mammals for spinal flexibility.

2. Appendicular Skeleton Joints

A. Fishes

- Pectoral/Pelvic Fins: Gliding joints for manoeuvrability.

- Lobe-finned Fishes (Sarcopterygii): Hinge-like joints in fins (pre-tetrapod adaptation).

B. Tetrapods

- Amphibians:

- Shoulder: Weakly developed synovial joints for crawling/jumping.

- Hip: Strengthened sacroiliac joint for weight-bearing.

- Reptiles:

- Ball-and-socket hips in dinosaurs for bipedalism.

- Snakes: Highly mobile vertebral joints for sidewinding.

- Birds:

- Fused sternocoracoid joint for flight muscle attachment.

- Synsacrum (fused pelvic vertebrae) for flight balance.

- Mammals:

- Shoulder: Rotator cuff for arm rotation (primates).

- Knee: Complex hinge with menisci for running.

IV. Evolutionary Milestones in Joint Development

1. Early Vertebrates (~500 MYA)

- Agnathans (Jawless Fish): Limited joints; notochord provided flexibility.

- Gnathostomes (Jawed Fish): Evolved synovial jaw joints for predation.

2. Transition to Land (~375 MYA)

- Sarcopterygians: Developed sturdy fin joints (pre-adaptation for limbs).

- Early Tetrapods (e.g., Acanthostega): Evolved weight-bearing limb joints.

3. Amniote Diversification (~320 MYA)

- Reptiles:

- Kinetic skull joints (snakes for swallowing large prey).

- Bipedal dinosaurs: Reinforced hip joints.

- Mammals:

- Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ): Enhanced chewing.

- Ball-and-socket hips: Efficient bipedalism (humans).

4. Specializations in Birds & Mammals

- Birds:

- Fused joints for flight efficiency.

- Pneumatic bones reducing weight.

- Mammals:

- Rotator cuff (shoulder stability).

- Knee menisci (shock absorption in runners).

Conclusion

Joints are pivotal in vertebrate evolution, enabling diverse locomotor and feeding strategies. From the rigid skull sutures of fish to the highly mobile synovial joints of mammals, their adaptations reflect ecological demands.