Chapter 3.3

Eye in Vertebrates (Aves and Mammals)

A. Structure and Function of Eye in Different Classes

Introduction

Definition and Evolutionary Significance

The vertebrate eye is a complex sensory organ that detects light and converts it into electrochemical impulses, enabling vision. Its evolution represents one of the most remarkable examples of functional convergence, with camera-type eyes appearing independently in vertebrates and cephalopods.

I. General Structure of the Vertebrate Eye

1. Cornea: Transparent outer layer that refracts light.

2. Lens: Focuses light onto the retina.

3. Retina: Contains photoreceptors (rods for low light, cones for colour).

4. Optic Nerve: Transmits visual information to the brain.

5. Accessory Structures: Iris (controls pupil size), sclera (protective outer layer).

II. The Avian Eye: Structure and Adaptations

General Anatomy

- Large eyes relative to skull size (e.g., owls’ eyes occupy 50% of skull volume).

- Pecten oculi: A vascular structure supplying nutrients to the retina (absent in mammals).

- Nictitating membrane: A translucent third eyelid for protection.

Diurnal Birds (e.g., Eagles, Hawks)

- High cone density for exceptional daytime vision.

- Fovea centralis: A deep pit in the retina for extreme acuity (eagles have 2x human visual resolution).

- Tetrachromatic vision: UV-sensitive cones enhance prey detection.

Nocturnal Birds (e.g., Owls)

- Rod-dominated retinas for superior night vision.

- Tubular eye shape maximizes light capture.

- Asymmetrical ears + binocular vision for precise prey localization.

Aquatic Birds (e.g., Penguins, Cormorants)

- Flat corneas for underwater focus.

- Red oil droplets in cones enhance contrast in dim waters.

III. The Mammalian Eye: Structure and Adaptations

General Anatomy

- Less variation in eye shape compared to birds.

- Tapetum lucidum in nocturnal species (reflects light for enhanced night vision).

Primates (High-Acuity Vision)

- Trichromatic vision (red, green, blue cones) in Old World monkeys and apes.

- Fovea specialization for detailed object recognition.

Nocturnal Mammals (e.g., Cats, Bats)

- Tapetum lucidum causes eyeshine.

- High rod-to-cone ratio (cats: 25:1).

Aquatic Mammals (e.g., Dolphins, Seals)

- Spherical lenses for underwater focus.

- Corneal flattening reduces refractive error when surfacing.

Ungulates and Prey Species (e.g., Deer, Horses)

- Horizontal pupils expand panoramic vision (300° field of view).

- Limited colour vision (dichromatic).

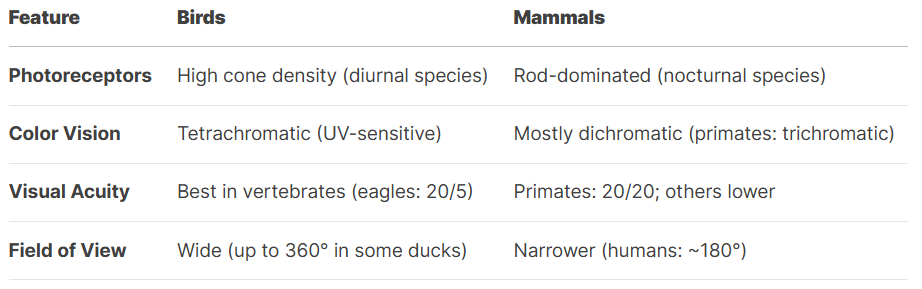

IV. Comparative Analysis of Avian and Mammalian Vision

IV. Major Evolutionary Milestones in Vertebrate Eye Development

1. Early Vertebrates (~500 MYA):

- Evolution of camera-type eyes from light-sensitive patches.

2. Mesozoic Birds (~160 MYA):

- Development of foveae and pecten oculi for flight precision.

3. Nocturnal Adaptations (~100 MYA):

- Tapetum lucidum in mammals; rod specialization in owls.

4. Aquatic Adaptations (~50 MYA):

- Spherical lenses in cetaceans and pinnipeds.

Conclusion

The vertebrate eye demonstrates extraordinary adaptive diversity, from the UV-sensitive retinas of birds to the light-amplifying tapeta of nocturnal mammals. Key evolutionary trends include: i) enhanced acuity in predatory birds and primates, ii) spectral sensitivity expansions (UV in birds, IR in some snakes), and iii) ecological specialization (aquatic flattening, nocturnal tubular eyes).