Chapter 2.2

Cranial skeletal system

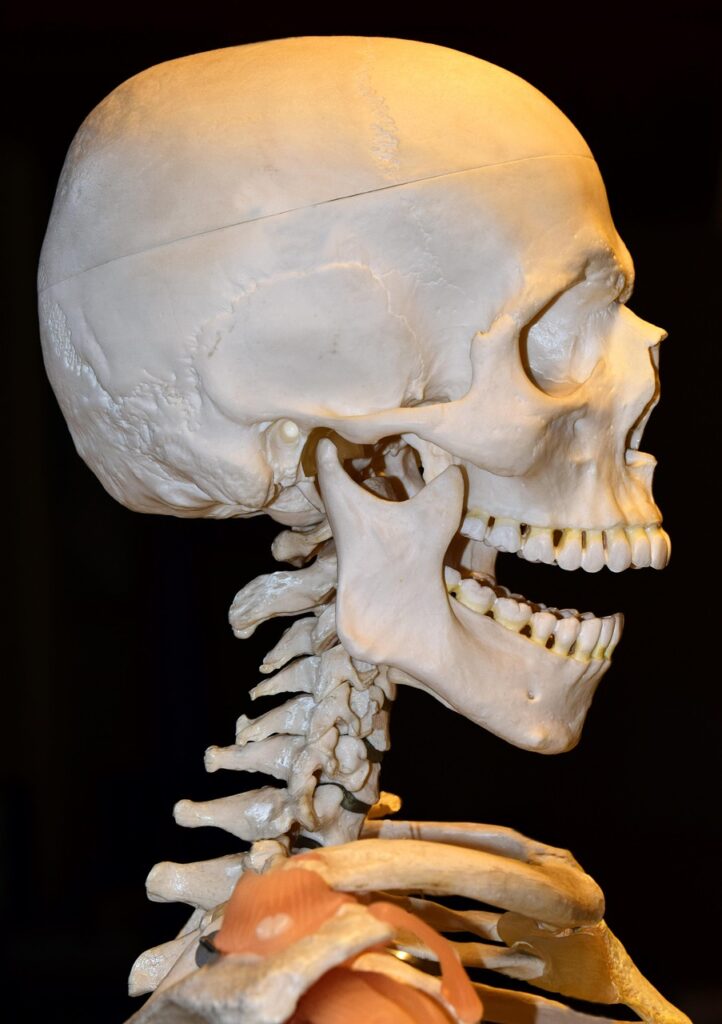

A. Basic Plan of Skull

Introduction

The vertebrate skull is a complex anatomical structure that serves as the primary protective and functional unit for the head. It houses the brain, sensory organs, and structures for feeding, respiration, and communication. The skull’s evolutionary history reflects adaptations to ecological niches, locomotion, and dietary habits. This lecture explores the basic plan of the vertebrate skull, focusing on its structural components, functional roles, and evolutionary trajectory. Key concepts include the splanchnocranium, neurocranium, chondrocranium, and the composite cranium.

I. Structural Components of the Skull

The vertebrate skull is a composite structure derived from two primary embryonic components:

- Neurocranium (brain case)

- Splanchnocranium (visceral skeleton)

- Dermatocranium (dermal bones contributing to the skull roof).

These components fuse during development to form the cranium, a unified structure with specialized regions.

1. Neurocranium

The neurocranium forms the protective casing around the brain and sensory organs (eyes, inner ears, olfactory organs). It is subdivided into:

- Chondrocranium: A cartilaginous scaffold in embryos, later replaced by bone in most vertebrates.

- Endochondral Bones: Bones formed via ossification of cartilage (e.g., occipital, sphenoid, ethmoid bones in mammals).

Functions:

- Protects the brain and sensory organs.

- Provides attachment sites for jaw muscles.

- Anchors the splanchnocranium and dermatocranium.

2. Splanchnocranium

The splanchnocranium originates from the pharyngeal arches (visceral arches) and forms the jaw, hyoid apparatus, and gill supports in aquatic vertebrates. Key derivatives include:

- Mandibular Arch: Forms the upper and lower jaws (except in jawless vertebrates like lampreys).

- Hyoid Arch: Supports the tongue and larynx.

- Branchial Arches: Gill supports in fish; repurposed in tetrapods (e.g., ear ossicles in mammals).

Functions:

- Facilitates feeding, respiration, and vocalization.

- Evolutionary pivot for jawed vertebrates (gnathostomes).

3. Dermatocranium

The dermatocranium comprises dermal bones forming the skull roof, jaws, and facial structures. These bones originate from intramembranous ossification (direct bone formation in connective tissue). Examples include:

- Frontal, parietal, and temporal bones (mammals).

- Maxilla and premaxilla (upper jaw).

Functions:

- Reinforces the skull.

- Protects superficial sensory organs.

- Contributes to jaw mechanics.

II. Embryonic Development: Chondrocranium

The chondrocranium is the cartilaginous precursor of the neurocranium, forming during early embryogenesis. It serves as a transient scaffold for endochondral ossification.

Key Stages:

- Parachordal Cartilage: Supports the hindbrain.

- Trabeculae Cranii: Forms the floor of the forebrain.

- Nasal Capsules: Enclose olfactory organs.

- Otic Capsules: Surround the inner ear.

In most vertebrates, the chondrocranium is replaced by bone, but it persists in cartilaginous fishes (e.g., sharks).

III. Functional Anatomy of the Skull

The skull integrates multiple functional systems:

1. Protection

- Brain Case: Neurocranium shields the brain from mechanical stress.

- Sensory Capsules: Otic (hearing), optic (vision), and nasal (smell) capsules protect sensory organs.

2. Feeding Mechanics

- Jaws: Derived from the splanchnocranium (mandibular arch), enabling predation and food processing.

Dentition: Teeth embedded in dermatocranial bones (e.g., maxilla, dentary).

3. Respiration

- Gill Arches: Splanchnocranium supports gills in fish.

- Hyoid Apparatus: In tetrapods, supports the tongue and laryngeal structures for air movement.

4. Sensory Integration

- Orbits: House eyes for vision.

- Tympanic Membrane: Transmits sound vibrations in tetrapods.

5. Musculoskeletal Attachment

- Muscle Origins/Insertions: Skull bones anchor muscles for jaw movement, head stabilization, and facial expression.

IV. Evolutionary Perspectives

The vertebrate skull has undergone profound evolutionary changes, driven by ecological pressures and developmental plasticity.

1. Agnatha to Gnathostomes

- Jawless Vertebrates (Agnatha): Lack a true splanchnocranium-derived jaw (e.g., lampreys).

- Jawed Vertebrates (Gnathostomes): Evolution of jaws from the mandibular arch (~420 MYA) enabled active predation.

2. Fish to Tetrapods

- Branchial Arches: Gill arches in fish were repurposed in tetrapods for hearing (e.g., stapes in the middle ear).

- Hyomandibula: Transformed into the columella (amphibians/reptiles) and stapes (mammals).

3. Amniote Diversification

- Diapsid vs. Synapsid Skulls:

- Diapsids (reptiles, birds): Two temporal fenestrae for muscle attachment.

- Synapsids (mammals): Single temporal fenestra, leading to advanced jaw muscles.

4. Mammalian Innovations

- Secondary Palate: Separates nasal and oral cavities, enabling simultaneous breathing and chewing.

Auditory Ossicles: Malleus and incus derived from reptilian jaw bones (quadrate and articular).

V. Comparative Anatomy of the Cranium

1. Fish

- Chondrichthyans (sharks): Retain a cartilaginous chondrocranium.

- Teleosts: Extensive dermatocranium with mobile jaw bones.

2. Amphibians

- Flat Skulls: Adapted for buccal pumping (respiration).

- Reduced Ossification: Retain cartilaginous elements (e.g., hyoid).

3. Reptiles

- Kinetic Skulls: Flexible joints (e.g., snakes) for swallowing large prey.

- Cranial Crests: Display structures in dinosaurs and birds.

4. Mammals

- Sutures: Fibrous joints allowing growth in juveniles.

- Brachycephalic vs. Dolichocephalic: Skull shape variations in domesticated species.

Conclusion

The vertebrate skull is a mosaic of evolutionary innovation, developmental plasticity, and functional specialization. Its basic plan – comprising the neurocranium, splanchnocranium, and dermatocranium – underscores the interplay between protection, feeding, and sensory integration. From jawless fish to mammals, the skull’s evolution reflects adaptive responses to ecological challenges, cementing its role as a cornerstone of vertebrate anatomy.

B. Temporal fossae – its function

Introduction

The temporal fossa (plural: fossae) is a critical anatomical feature of the vertebrate skull, playing a pivotal role in biomechanics, feeding, and evolutionary adaptation. Defined as the depression on the lateral surface of the skull behind the orbit, it serves as an attachment site for jaw muscles and reflects ecological and functional specializations. This lecture explores the definition, functions, classification of skull types based on temporal fossae, and their evolutionary significance across vertebrates.

I. Defining the Temporal Fossa

1. Anatomical Boundaries

The temporal fossa is a shallow depression located on the lateral aspect of the skull, bounded by the following structures:

- Anteriorly: Posterior margin of the orbit (varies by species).

- Posteriorly: Temporal crest or occipital region.

- Dorsally: Parietal and frontal bones.

- Ventrally: Zygomatic arch (cheekbone) in mammals.

In many vertebrates, the fossa is perforated by temporal fenestrae (openings), which are key to classifying skull types.

2. Temporal Fossa vs. Temporal Fenestra

- Temporal Fossa: The depression housing jaw muscles.

- Temporal Fenestra: Openings within the fossa that reduce skull weight and provide space for muscle expansion.

II. Functions of the Temporal Fossa

The temporal fossa is integral to skull function, particularly in feeding and locomotion.

1. Muscle Attachment and Feeding Mechanics

- Temporalis Muscle: The primary muscle occupying the fossa. Contracts to elevate the jaw during biting/chewing.

- Biomechanical Advantage: Enables powerful jaw closure by increasing leverage.

- Adaptive Radiation: Variations in fossa size correlate with dietary habits (e.g., large fossae in carnivores for strong bites).

2. Skull Lightening and Structural Integrity

- Fenestration: Fenestrae reduce skull mass without compromising strength.

- Stress Distribution: Redirects mechanical forces during feeding, minimizing fractures.

3. Thermoregulation and Vascularization

- Heat Dissipation: In some species, fossae house blood vessels that aid in cooling.

- Sensory Integration: Proximity to the braincase may link to neural or vascular networks.

4. Evolutionary Signaling

- Sexual Dimorphism: Enlarged fossae in males (e.g., gorillas) for display or combat.

- Ecological Niches: Fossa morphology reflects predatory, herbivorous, or omnivorous lifestyles.

III. Classification of Skulls Based on Temporal Fenestrae

The number and arrangement of temporal fenestrae classify skulls into four major types:

1. Anapsid Skull

- Features: No temporal fenestrae; solid bony covering.

- Examples: Extinct stem reptiles (e.g., Captorhinus), modern turtles (controversial; some argue turtles secondarily lost fenestrae).

- Function: Maximizes protection at the cost of muscle flexibility.

2. Synapsid Skull

- Features: Single temporal fenestra below the postorbital and squamosal bones.

- Examples: Non-mammalian synapsids (e.g., Dimetrodon), mammals.

- Function: Accommodates larger jaw muscles (e.g., temporalis, masseter), enabling complex chewing.

3. Diapsid Skull

- Features: Two temporal fenestrae: upper (supratemporal) and lower (infratemporal).

- Examples: Modern reptiles (lizards, snakes, crocodilians), birds, dinosaurs.

- Function: Supports multidirectional muscle attachments for diverse feeding strategies.

4. Euryapsid Skull

- Features: Single upper temporal fenestra (homoplastic with diapsids).

- Examples: Extinct marine reptiles (e.g., ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs).

- Function: Likely adapted for aquatic locomotion and feeding.

IV. Evolution of Temporal Fossae & Fenestrae in Vertebrates

The temporal fossa and fenestra are a hallmark of amniote evolution, reflecting adaptations to terrestrial life and ecological diversification.

1. Early Amniotes and the Anapsid Condition

- Origin: Early amniotes (~320 MYA) lacked fenestrae (anapsid skull).

- Advantage: Robust skulls suited for low-energy diets (e.g., insects, plants).

- Limitation: Restricted jaw muscle size and mobility.

2. Synapsid Innovation: Rise of Mammalian Ancestors

- Permian Synapsids: Evolution of a single fenestra (~300 MYA) allowed larger jaw muscles.

- Therapsids: Advanced synapsids (e.g., Thrinaxodon) developed stronger bites, precursors to mammalian mastication.

- Mammalian Transition: Fenestra expanded into a broad fossa, enabling heterodont dentition and precise occlusion.

3. Diapsid Dominance: Reptiles and Birds

- Carboniferous Diapsids: Split into archosaurs (dinosaurs, crocodilians, birds) and lepidosaurs (lizards, snakes).

- Fenestrae Functions:

- Supratemporal Fenestra: Anchored neck muscles in dinosaurs.

- Infratemporal Fenestra: Lightened the skull in birds for flight.

- Avian Modifications: Fusion of skull bones reduced fenestrae but retained fossae for muscle attachment.

4. Euryapsids and Marine Adaptations

- Mesozoic Marine Reptiles: Euryapsid skulls convergently evolved in ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs.

- Hydrodynamic Efficiency: Fenestrae reduced drag while retaining muscle attachments for aquatic predation.

5. Modern Variations

- Mammals: Synapsid fossa integrated with the zygomatic arch for sagittal crests (e.g., gorillas).

- Snakes: Loss of temporal bars (kinetic skulls) for swallowing large prey.

- Birds: Fusion of fossae into a streamlined cranium for flight.

V. Case Studies in Functional Morphology

1. Carnivorans vs. Herbivores

- Carnivores (e.g., lions): Deep, narrow fossae for high bite force.

- Herbivores (e.g., horses): Broad, shallow fossae for sustained grinding.

2. Human Temporal Fossa

- Reduced Size: Reflects omnivorous diet and smaller temporalis muscle.

3. Extinct Giants: Tyrannosaurus rex

- Massive Fossae: Accommodated jaw muscles generating ~8,000 psi bite force.

VI. Evolutionary Theories and Debates

1. Fenestration Hypotheses

- Muscle Expansion Theory: Fenestrae evolved to allow jaw muscles to bulge during contraction.

- Craniokinesis Hypothesis: Fenestrae enabled skull flexibility in reptiles for prey capture.

2. Developmental Genetics

- Role of Runx2: Gene regulating osteoblast differentiation, linked to fenestra formation.

- Neural Crest Cells: Contribution to dermal bone patterning around fossae.

3. Secondary Closure in Turtles

- Controversy: Whether turtles lost fenestrae (ancestral anapsid) or re-evolved a solid skull.

Conclusion

The temporal fossa exemplifies the interplay of form and function in vertebrate evolution. From the anapsid skulls of early amniotes to the specialized fenestrae of mammals and reptiles, this structure underpins feeding efficiency, ecological adaptation, and phylogenetic diversity. Understanding its anatomy and evolution provides insights into biomechanical constraints, paleoecology, and the origins of modern vertebrates.

C. Jaw Suspension and its types

Introduction

The jaw is a defining feature of vertebrates, enabling feeding, communication, and ecological adaptation. Jaw suspension – the mechanism by which the jaw articulates with the skull – varies across taxa, reflecting evolutionary innovations and functional demands. This lecture explores the structure, functions, types of jaw suspension, and evolutionary trajectory from early fishes to mammals, highlighting biomechanical and phylogenetic significance.

I. Structure of the Jaw

The jaw comprises skeletal elements derived from the mandibular arch (first pharyngeal arch), with modifications across vertebrates:

1. Basic Components

- Upper Jaw (Palatoquadrate): In fish, a cartilaginous or bony structure forming the roof of the mouth.

- Lower Jaw (Meckel’s Cartilage): Cartilaginous precursor in embryos, ossifying into the mandible in most vertebrates.

- Articulation Points: Joints connecting the jaw to the neurocranium (e.g., quadrate-articular joint in reptiles, temporo-mandibular joint in mammals).

2. Comparative Anatomy

- Fish: Jaw composed of palatoquadrate (upper) and Meckel’s cartilage (lower), often supported by the hyomandibula.

- Mammals: Single dentary bone (mandible) articulating with the squamosal bone via the temporomandibular joint (TMJ).

- Reptiles/Birds: Multiple bones (e.g., articular, quadrate) forming the jaw joint.

II. Functions of Jaws

Jaws serve diverse roles shaped by ecological niches:

1. Feeding Mechanics

- Prey Capture: Protrusible jaws in fish (e.g., teleosts) enhance suction feeding.

Mastication: Mammalian jaws enable precise occlusion for grinding (herbivores) or shearing (carnivores).

Filter Feeding: Baleen whales use keratinous plates instead of teeth.

2. Non-Feeding Roles

- Vocalization: Jaw movements modulate sound in humans and birds.

- Tool Use: Parrots and primates manipulate objects.

- Defense/Display: Tusks in elephants, deers, and hogs.

III. Types of Jaw Suspension

Jaw suspension mechanisms are classified based on skeletal attachments:

1. Autostylic Suspension

- Definition: Jaw attached directly to the cranium via the palatoquadrate. (Modified autostylic system with a secondary jaw joint are known as Metautostylic Suspension).

- Examples: Lungfishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. Metautostylic suspension is seen in advanced mammals (including humans).

- Advantages: Stability for powerful bites; limited mobility.

2. Amphistylic Suspension

- Definition: Dual attachment via palatoquadrate (anterior) and hyomandibula (posterior).

- Examples: Early sharks (e.g., Cladoselache).

- Advantages: Moderate mobility; transitional form.

3. Hyostylic Suspension

- Definition: Jaw suspended primarily by the hyomandibula (second pharyngeal arch).

- Examples: Modern sharks, teleost fishes.

- Advantages: High mobility for jaw protrusion and suction feeding.

4. Craniostylic Suspension

- Craniostylic jaw suspension, a type of jaw attachment in mammals, involves the fusion of the upper jaw (maxilla) to the skull (cranium) along its length. This fusion creates a stable and strong connection, enabling efficient chewing and biting. In this type of jaw suspension, the lower jaw articulates with the skull at the mandibular fossa, a specific region of the squamous bone.

IV. Evolution of Jaw Suspensorium

The jaw evolved from pharyngeal arches in early vertebrates, with key transitions:

1. Jawless Vertebrates (Agnathans)

- Pre-Jaw Era: Hagfish and lampreys lack true jaws, using a rasping tongue for feeding.

2. Origin of Jaws (Gnathostomes)

- Mandibular Arch: First pharyngeal arch differentiated into jaws (~420 MYA).

- Hyoid Arch: Second arch became the hyomandibula, supporting jaw suspension.

3. Fish to Tetrapods

- Early Fish: Hyostylic suspension dominated, enabling suction feeding.

- Transitional Forms: Tiktaalik (fishapod) retained fish-like jaws but developed weight-bearing limbs.

- Tetrapods: Shift to autostylic suspension, freeing the hyomandibula for hearing (e.g., stapes in mammals).

4. Mammalian Innovations

- Dentary-Squamosal Joint: Reptilian quadrate and articular bones evolved into incus and malleus (middle ear ossicles).

- TMJ Development: Enhanced chewing efficiency via muscle specialization (e.g., masseter, temporalis).

V. Functional Adaptations Across Taxa

1. Fish

- Sharks: Hyostylic suspension for rapid jaw protrusion.

- Teleosts: Modified hyostylic jaws with pharyngeal teeth for processing food.

2. Amphibians/Reptiles

- Frogs: Autostylic jaws for capturing prey with sticky tongues.

- Snakes: Kinetic skulls with flexible ligaments for swallowing large prey.

3. Mammals

- Carnivorans: Robust TMJ for shearing meat.

- Ungulates: Broad mandibles for grinding fibrous plants.

Conclusion

Jaw suspension exemplifies the interplay of form, function, and evolution. From the hyostylic mechanisms of sharks to the metautostylic precision of mammals, these adaptations underscore vertebrate diversity and ecological success.